xken health

Early detection and personalized therapy for chronic diseases, including tumor diseases, through proteomic analysis from blood filtrate and urine.

- risk-free - painless - reliable -

Chronic diseases

The disruptive paradigm shift of finally defining chronic diseases at the molecular level, thus enabling early detection and the allocation of individually effective medications to patients, has prompted the EU Commission to identify proteomics as the key technology with the highest market relevance out of 13,000 funded innovations [1].

Since 2002, over 100 clinical trials have been conducted, involving 1,200 leading physicians and scientists from over 95 university hospitals worldwide. The results have been published in over 450 articles in renowned scientific journals and represent the current state of medical knowledge.

The UN identifies chronic diseases as a scourge of Western civilization and places them on the same threat level as Ebola [3]. The cause is their much too late detection. Currently, these diseases are not recognized at the molecular level, where they originate, but only based on massive functional impairment of the affected organ. However, diseases only arise at the molecular level. The cellular, disease-related changes are controlled solely by proteins. Which proteins act, at what time, and what the underlying causes are can only be deciphered and determined within the complex context of a body sample, from the proteome (the entirety of proteins).

For the first time, only the proteomic analysis from xken® health can define diseases on a daily basis at the molecular level where they originate. This deciphers the entire molecular course of disease in humans via the proteome and specifies it for each individual disease. The earliest onset of diseases can be identified via the proteome, as can the differentiation between diseases and which medications – including nutrients – the patient responds to. This makes the currently only available medical treatment possible for the first time on a complex, reliable molecular, scientific basis: the proteome.

Kidney disease

Approximately one in ten people suffers from chronic kidney disease (CKD) – often unnoticed, as the disease causes no noticeable symptoms in its early stages. It is often only diagnosed too late, based on clinical symptoms, when kidney damage is already advanced. By then, effective treatment is no longer possible. The progression of organ damage can only be slowed, not stopped. Left untreated, CKD leads to kidney failure and kidney toxicity, and death within a few days. Renal replacement therapy, such as dialysis, has significant long-term consequences, and even a successful transplant (approximately 30% of transplants are rejected) offers only a limited lifespan. Chronic kidney disease is associated with a significantly reduced life expectancy – depending on the severity of the disease, it can be shortened by up to 18 years.

Cardiorenal syndrome - the interplay of heart and kidney!

Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) refers to the simultaneous occurrence of heart and kidney dysfunction. Dysfunction in one organ leads to impairment in the other. Numerous studies have shown that cardiovascular diseases are significantly more common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Likewise, many patients with heart failure suffer from impaired kidney function. Both organs are interconnected through many mechanisms, including blood pressure regulation, high energy demands, and vascularization. Consequently, both organs are also affected by systemic pathological processes such as endothelial damage (damage to the inner lining of blood vessels), inflammation, or fibrosis (excessive formation of connective tissue). Key pathophysiological mechanisms of CRS include impaired glucose metabolism, neurohormonal activation, and oxidative stress. Growing scientific evidence indicates that fibrosis plays a crucial role in disease development. In many cases, fibrosis develops even before the clinical presentation of CRS. Novel biomarkers that measure changes in collagen metabolism in the extracellular matrix of the heart and kidneys allow for the early detection of subclinical fibrotic remodeling processes. This opens up promising possibilities for personalized therapy of cardiorenal syndrome.

The key to successful treatment lies in early and targeted therapy, which can slow down or even prevent the progression of the disease. The earlier the disease is diagnosed, the more effective lifestyle changes—including improved diet and exercise—will be, with or without medication. A range of medications are now available to patients that can slow the progression of CKD. However, not all patients respond equally to treatment. Until now, there has been no reliable method for predicting which therapy will be most suitable for a particular patient.

Proteomic analysis (PA) – a breakthrough in the diagnosis and therapy of chronic kidney disease and cardiorenal syndrome – based on the current state of medical/scientific knowledge and published literature and studies:

Proteome analysis from urine offers a completely new approach to the early detection and personalized treatment of CKD. It enables:

- Early detection of kidney disease – before irreversible organ damage occurs, so that early intervention is possible.

- Determining the exact type of kidney disease – without the risks and limitations of an invasive kidney biopsy, solely based on the specific proteome pattern.

- Personalized therapy recommendation – by predicting which treatment is best suited for the individual patient.

Benefits for patients

The application of proteomic analysis offers numerous advantages:

Increased life expectancy and preservation of kidney function through early diagnosis and targeted therapy.

Optimized, personalized treatment with the best possible therapy for the individual patient.

Avoidance of invasive procedures such as kidney biopsy through non-invasive urine analysis.

a. Early detection

Modern, non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic methods are now available, enabling reliable diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapies (see figure). Therefore, molecular diagnostics should be considered for patients with relevant risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, age, obesity, potentially impaired renal function, unspecified urinary abnormalities). One non-invasive method for the early detection or exclusion of chronic kidney disease (CKD) that has been tested in numerous studies is the CKD273 urine proteome pattern, based on an AI algorithm that assesses 273 peptides and proteins in urine [4].

b. Liquid biopsy – instead of a biopsy!

Certain relevant diseases can be ruled out or confirmed based on the medical history, imaging procedures and the presence of diabetes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proposed decision tree for a non-invasive, biomarker-based diagnostic approach in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Based on current scientific literature, available prognostic and predictive biomarkers for supporting CKD management have been combined to provide guidance for their application. The figure shows the available biomarkers and their potential uses for specific diseases. If this decision tree does not lead to a definitive diagnosis, additional biomarkers—particularly in rare diseases—should be considered depending on the clinical presentation. If a definitive diagnosis and sufficiently reliable treatment recommendations cannot be derived, the invasive diagnostic approach via kidney biopsy remains the last option.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) caused by circulatory problems can usually be diagnosed reliably based on the patient's medical history. Characteristic imaging features also allow for the diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), as well as obstructive kidney diseases such as congenital urogenital tract obstructions (CAKUT). In structural kidney diseases not caused by diabetes or hypertension, the next diagnostic step is the differential diagnosis. Specific urine peptide patterns [5, 6] can be used for this purpose. In cases of glomerular, nephrotic, and non-selective proteinuria, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN/C3GP), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), minimal change disease (MCGN), membranous nephropathy (MN), or renal amyloidosis should be considered. Renal amyloidosis can be confirmed or ruled out by the ratio of lambda to kappa light chains. Membranous nephropathy (MN) can be detected by specific autoantibodies. If neither an abnormal light chain profile nor autoantibodies for MN are present, MCGN or FSGS are likely.

Inflammatory glomerulopathies are characterized by the excretion of erythrocytes in the urine. Further differentiation is possible through highly specific urine proteome patterns or genomic analyses. Alport syndrome can be diagnosed based on dysmorphic erythrocytes in the urine as well as by known mutations in the collagen IV gene. IgA nephropathy (IgAN), the most common glomerulonephritis worldwide, can be detected with high accuracy by the urine proteome pattern IgAN237 [7].

Rapid kidney failure, combined with proteinuria and dysmorphic erythrocytes in the urine, suggests disease of the entire glomerular compartment with extracapillary proliferation. Goodpasture syndrome can be diagnosed by detecting antibodies against the glomerular basement membrane. In autoimmune vasculitis, ANCA antibodies are indicative. Lupus nephritis can be diagnosed by detecting antinuclear and dsDNA antibodies.

Thanks to decades of research, it is now possible to assess the diagnostic reliability of biomarkers, genetic analyses, and proteomic patterns using existing histomorphological gold standards. The first steps toward a non-invasive "liquid kidney biopsy" have already been taken. This technology can already be used today and makes it possible to avoid a kidney biopsy and its associated risks.

c. Determination of medications

Based on the proteomic pattern in urine, it is possible to predict which medications or other therapeutic interventions (e.g., lifestyle changes, diet, etc.) the patient will respond to [8]. In this way, the optimal, personalized therapy can be determined for each patient.

The current diagnosable advanced state of the disease and the therapy that only then begins

Currently, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is usually diagnosed only when significant organ damage is already present. This is done either by measuring the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which indicates a reduction in kidney function of more than 50%, or by detecting increased albumin excretion in the urine. Since 50% of patients with impaired renal filtration and significant kidney damage showed no abnormality in urinary albumin excretion (albumin is a very large protein), this parameter is unsuitable for detecting the early stages of the disease. This is the conclusion of the FDA, which, in its Letter of Support, advocates for proteomic analysis [2].

To accurately determine the underlying kidney disease, a kidney biopsy has often been performed. This involves taking a tissue sample from the kidney using a hollow needle, which is then examined by a specialist (pathologist). However, this procedure is highly invasive, carries significant risks, and is not suitable for all patients.

Conclusion

Proteomic analysis of urine represents a groundbreaking development in nephrology. It makes it possible to detect CKD at an early stage, prevent organ failure, and tailor treatment to the individual patient. This can not only prevent the need for dialysis or transplantation in many cases, but also significantly improve the life expectancy and quality of life of those affected.

Tumor diseases

Cancer can occur in various organs of the body and originates from different cell types. Most cancers begin on the internal and external surfaces of the body.

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common type of cancer in men in Germany [9]. The number of new cases of prostate cancer in 2022 was approximately 74,895. Prostate cancer rarely occurs before the age of 50. In older men, PCa is found in the majority of patients, but in most cases it is of low malignancy [2].

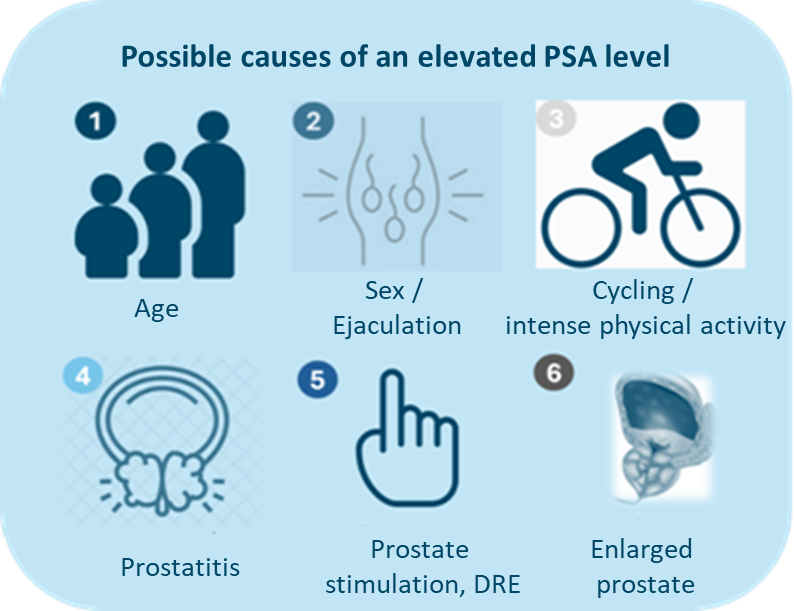

The PSA test is the most commonly used test for prostate cancer screening. The PSA test measures prostate-specific antigen. It is not a specific biomarker for detecting prostate cancer. It is merely an indicator of changes in the prostate. These changes can have many causes unrelated to prostate cancer (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Possible causes for an elevated PSA level.

Sources of error in the assessment of the PSA value [11]

- Intra-individual variations: PSA values can fluctuate by +/-15%.

- Measurement method: There are variations between laboratories (up to about 5%).

- Handling of samples: Proper handling is crucial, with specific stability periods for centrifuged samples.

- Urinary tract infection: Infections can cause very high PSA levels (>100ng/ml), which can take up to a year to normalize.

- Acute urinary retention: This condition moderately increases PSA levels.

- Biopsy: PSA tests should be postponed for at least one month after biopsies.

- Hypogonadism: PSA production depends on testosterone levels and affects PSA levels in men with low testosterone.

- The production of prostate-specific antigen is androgen-dependent, and 5α-reductase inhibitors (e.g., finasteride, dutasteride), used in benign prostatic hyperplasia, lower the PSA level by 50%.

The dilemma of prostate cancer diagnosis using PSA - the cause of unnecessary biopsies and over-treatment!

The only necessary corrective to the predominantly false suspicion of cancer based on elevated PSA levels is currently the invasive biopsy, which is associated with significant side effects. However, prostate biopsy results often yield false positives and false negatives, leading to overtreatment in many cases: 90% of all radical prostate treatments are unnecessary, resulting in significant limitations – incontinence/impotence – and furthermore, unnecessary risks. The results of the ProtecT study [12], which showed overtreatment in 90% of all treatments and biopsies, have led to a crisis of confidence among patients in medicine as a whole.

The probability of the biopsy needles missing the tumor is high. A higher number of biopsies – up to 12 needles can be inserted into the prostate instead of 6 – and repeat biopsies have been intended to compensate for this. However, the increased number of biopsies and repeat biopsies also exponentially increase the risks of inflammation, tumor metastasis, and thus health hazards in prostate cancer diagnostics.

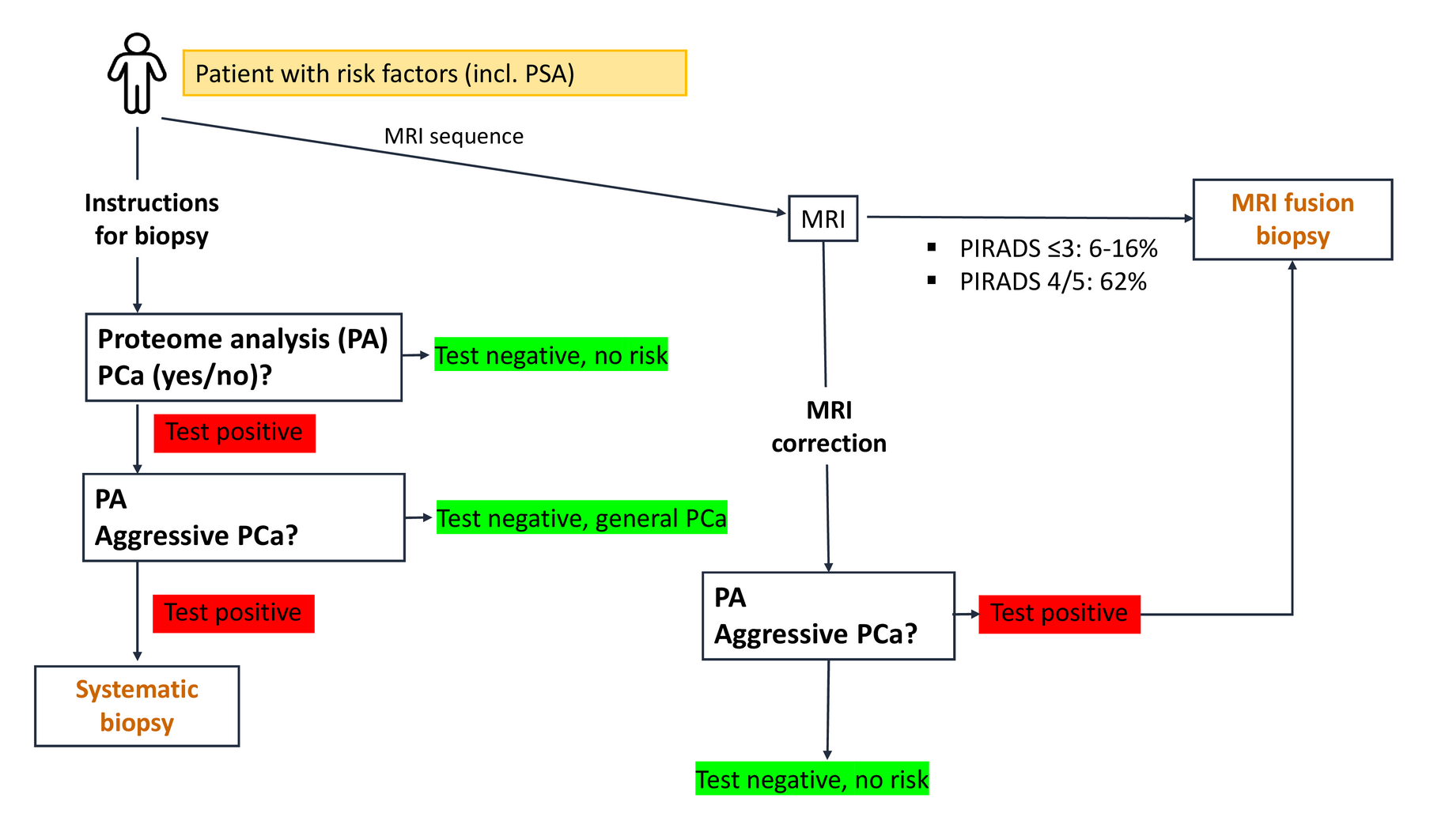

Figure 3: Proposed decision tree for a non-invasive, biomarker-based diagnostic approach to prostate cancer (PCa). The figure shows the available diagnostic options. If a definitive diagnosis and a sufficiently reliable treatment recommendation cannot be derived, the invasive diagnostic approach via prostate biopsy remains the last option.

Before performing an invasive prostate biopsy in a patient with an elevated PSA level, other, non-invasive options should be considered (see Figure 3). This should increasingly be achieved using mpMRI and fusion biopsy. MRI has a pooled sensitivity of 91% and a pooled specificity of 37% for clinically significant cancer (ISUP ≥GG2) [11]. This means that 63% of patients who would undergo a biopsy would not have clinically significant cancer.

Another limitation of MRI is that 40–50% of men undergoing an MRI do not receive a clear indication of the presence of a significant tumor (PIRADS ≤3). Because the result is ambiguous and the risk of significant prostate cancer is only 6–16%, these patients are usually subjected to an invasive biopsy [11]. Health insurance companies generally do not cover the costs of the preceding MRI, which amount to approximately €1,000 (up to €2,000), only the invasive biopsy.

To correct PSA and MRI results, the EAU guidelines recommend risk stratification using alternative methods or biomarkers to avoid magnetic resonance imaging scans and biopsy procedures.

Proteomics analysis, with its scientific definition and identification, represents the current state of medical knowledge.

Why is this methodological approach so precise? Cells constantly need to renew themselves. Some do so quickly, others take weeks. If the signals for regeneration are faulty, unnecessary cells can form. If this is not compensated for by the body's comprehensive mechanisms, so-called malignant cells establish themselves. This is the basis for cancer development, the growth of which is furthered by inflammatory processes in the body, which can also be caused by the environment and a contaminated food chain. Since these cellular changes in the body are controlled exclusively by proteins, proteomic analysis is the first method capable of mapping these alterations. Confirmation in studies relies on the limitations of methodological approaches such as PSA and biopsy. It can be assumed that the accuracy of proteomic analysis is even qualitatively better than currently reported. According to the available studies, proteomic analysis is extremely useful both in its detection with a negative predictive value of 93-94% [13, 14, 15] and also in determining whether dangerous prostate cancer is present, and should be performed after an abnormal PSA finding before invasive diagnostics or therapies.

Conclusion

Proteomic analysis not only corrects the PSA test in its predominantly false-positive findings, but due to its scientific methodological approach, it is also able to detect previously undetected serious cancer findings.

References

- https://innovation-radar.ec.europa.eu/innovation/58774

- https://www.fda.gov/media/99837/download

- UN-Resolution A/RES/66/2 (2011)

- Good et al., Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 2010, 9(11):2424-37.

- Siwy et al.,Nephrol Dial Transplant2017, 32(12):2079-2089.

- Mavrogeorgis et al.,Nephrol Dial Transplant2024 Feb 28;39(3):453-462.

- Rudnicki et al.,Nephrol Dial Transplant2021, 37(1):42-52.

- Jaimes Campos et al., Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16(9):1298.

- Robert Koch Institute, Center for Cancer Registry Data, database query with data up to 2022.

- Haas et al., Can J Urol. 2008, 15(1):3866-71.

- Cornford et al., Eur Urol. 2024, 86(2):148-163.

- Hamdy et al., N Engl J Med. 2023, 388(17):1547-1558.

- Frantzi et al., Br J Cancer. 2019, 120(12):1120-1128.

- Frantzi et al., World J Urol. 2022, 40(9):2195-2203.

- Frantzi et al., Pathobiology 2024, 11:1-10.